So now you know what makes a half-hour dramedy what it is and you know how to get to the core of what yours should be about. The next step is writing the actual script, or punching up one you’ve already written.

As promised, I analyzed the structure (length, act breaks, number of characters, and narrative arc) of a group of half-hour dramedy pilots. I found that all the pilots I studied were structured in a very similar way, even across networks.

I did a less in-depth version of this analysis for one-hour drama pilots here.

I share this information not to give you a paint-by-numbers template because there are hundreds of TV series out there that take a paint-by-numbers approach to storytelling and most are instantly forgettable. But if you write about something that matters to you and set it in a world you find interesting, comparing its structure to this template might help you see what your story is missing or why it feels too slow or too rushed.

There are definitely some outliers, like FX’s Better Things, which is more of a stream of consciousness “slice of life” pilot, but even that episode has act breaks and still loosely follows the pattern of the other shows I studied, just in a quieter, more subtle way. (It’s a beautiful pilot that I recommend watching even if it’s hard to take many structural lessons from it.)

Better Things on FX

Amazon’s Transparent is another pilot that doesn’t fit comfortably in the structure of most half-hour dramedies because each season is written as a five-hour movie. The first episode is really just the first half of Act 1 leading up to the inciting incident. So it does have a formal structure, it’s just not TV structure. I would not recommend attempting this unless, like Jill Soloway, you already have a full season order from a streaming network.

How Long Should Your Pilot Be?

The half-hour dramedy pilots I studied all had 4 or 5 acts (usually 5), including any teaser or tag that might be included. Across those acts, the episodes were divided into 11-16 scenes, usually in the 14-15 range. These pilots were all 21-27 minutes long (most were 21-22 minutes), but one minute doesn’t always equal one page. Note that at least one of the major TV writing contests requires half-hour pilots to be at least 25 pages. I assume the higher page count is because comedies have historically had more quick back and forth dialogue which means more line breaks on the page in a short period of screen time.

So your pilot would feel similar to a produced pilot if it was 5 acts (possibly including a teaser and/or tag), divided into 14-15 scenes of about 1.5-2 pages each (on average).

I don’t mean that prescriptively, but if something about your script feels off, that’s a place to look if your script differs wildly from this very common template.

How Many Characters Should I Introduce?

I read a lot of pilots and some of them feel too thin because there aren’t enough characters to create conflicts between, while others feel overwhelming because there are too many characters to keep straight in your mind.

Of course, it’s much less about the number of characters you have and more about how you differentiate those characters and how you make use of them. Every character should represent a different side of the argument you’re making or the theme you’re exploring, and those characters should have between them inherent potential for conflict and inherent potential for connection in as many different combinations as possible.

What really makes a script feel like it has “too many characters” is when multiple characters are serving the same purpose in the story, and what makes a script feel like it has “too few characters” is when there aren’t enough built-in opportunities for conflict or connection between characters.

What really makes a script feel like it has “too many characters” is when multiple characters are serving the same purpose in the story, and what makes a script feel like it has “too few characters” is when there aren’t enough built-in opportunities for conflict or connection between characters.

This is why shows like The Walking Dead (in later seasons particularly) keep piling on more and more new characters – it feels like there aren’t enough characters even though there are already so many, but it’s actually just that the characters they already have don’t have enough different combinations of naturally-occurring opportunities for conflict and connection between them. This is a common problem I see in pilots I read.

All of that said, the pilots I studied had between 10-20 speaking parts, and of those speaking parts, there were only 2-4 main characters. I define “main character” here as a character who is in a lot of scenes and will obviously play a major role in the series going forward with their own problems to solve and a meaningful character arc. This is important because if you have more than 3 or 4 main characters in a half-hour pilot, it’s going to be hard for the audience to keep track of and care about all of them.

People of Earth on TBS

We also see between 3-10 secondary characters introduced. I define “secondary character” here as a character with a name who will be coming back in future episodes. These characters usually don’t have their own goals, problems, and arcs, though they might develop them in future seasons. These are characters like Dory’s boss in Search Party, the priest in People of Earth, or Sam’s dad in Better Things.

These kinds of characters are important because while they do not initially have goals and problems of their own (or at least not ones we’re invested in), they can create or complicate conflicts for our main characters, and they’re waiting in the wings in later episodes when you start running out of story ideas for your protagonists.

Last, these pilots had between 2-10 minor characters, which I define here as characters that only have a line or two, usually don’t have a real name, and most likely will not return in future episodes. These are characters like “Bellhop” or “Protestor #2.”

It’s worth noting that the line between “main character” and “secondary character” can be blurry. For example, in the pilot of The Good Place I considered only Michael, Eleanor and Chidi to be main characters, while I classified Tahani, Jianyu, and Janet as secondary characters. This is accurate based on the pilot, but if you keep watching the show, those three secondary characters take on a much bigger role and some minor characters step up as new secondaries. This happens on most series, but for the purpose of this analysis, you should think of your characters in the context of just your pilot.

What Happens in Each Act?

First Section (Teaser or Act 1)

The first section (either a teaser or Act 1) is 1-2 scenes and lasts between 1-3 minutes. In this section, we establish the basic premise (what this show is about on the most logline-y level) and the tone (funny and action-packed, heightened reality, a musical, dreamlike and tender, etc.).

These are really important concepts that are missing from the first section of most pilots I read. We don’t need to understand every complexity of the plot and theme in the first three minutes of your pilot, but we should be able to state the logline of your series (or at least the first half of it) based on these three minutes.

It’s also important that we get the tone of your show – if it’s a show that’s mostly funny, the first scene should be funny. If it’s going to have scary parts or a heightened, fantastical quality, that tone should be presented in the very first scene so we understand what we’re watching and can view it through the right lens. If it’s a musical, there better be a song real quick.

In this first section, we also usually meet the main character, but sometimes not if it’s a teaser. If we do meet the main character, we might also meet one or two other main or secondary characters, but almost certainly not all of them.

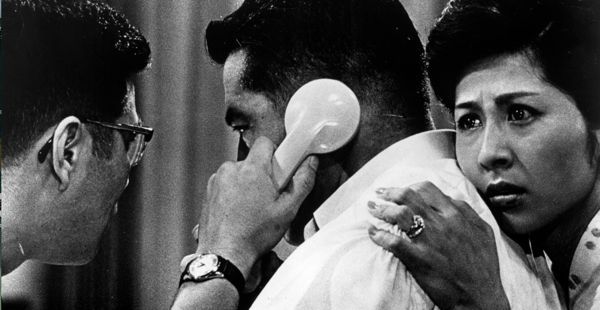

Search Party on TBS

Second Section (Act 1 or Act 2)

The second section (either Act 1 or Act 2) is 3-6 scenes and lasts between 3-8 minutes. In this section, we meet the rest of the main characters. We learn what we need to know about the world. The main problem of the series/season/episode is established.

When I say that we meet the main characters, it’s not enough that they are just physically on screen. We should understand their deal, at least on a basic level. What is one word that most strongly describes their personality? Of course your characters are more complex than can be summed in one word, and we’ll hopefully have a chance to learn this over the course of many episodes and seasons, but there’s probably one quality that describes them most simply: arrogant, insecure, sullen, idealistic, selfish, gullible, logical, etc. That one word should come across right away so the audience has something to hold onto about this character, even if later we will come to understand them in a more nuanced way (which we hopefully will).

This is also where we’ll probably meet the antagonist if there is one. Remember that an antagonist doesn’t have to be a mustache-twirling supervillain, just a character whose choices, values, and desires stand in opposition to our protagonist.

When I say we learn what we need to know about the world, this is sometimes as simple as an establishing shot of a city skyline and a scene in the office that makes clear what everyone’s job is in a company. In other shows, the world is unfamiliar and complicated and so a lot more time must be dedicated to explaining how it works.

If your pilot is in an unfamiliar, complicated world, you’ll need to figure out exactly what the audience needs to understand in the first episode to understand and enjoy the show, and then communicate that in as succinct and entertaining of a way as possible. You don’t need to explain every single fact about your world in the pilot, but you need to explain enough that they feel grounded in the story. Watch the pilot of The Good Place for a great example of how to do this.

The Good Place on NBC

If you have any unusual elements like magic or musical numbers, it’s especially important to introduce these right away so it doesn’t feel like it’s coming out of nowhere later. Similarly, if your world has a complicated geography that’s important to understand, you might need to spend some time laying that out visually.

Last, this is the section where you’ll introduce the main problem of the series (or the problem of the season or of the episode). The problem might be as small as “teen girl doesn’t get along with her mother” or it might be as large as “aliens have invaded a small town” or “a mild-mannered accountant must solve a murder.” Whatever the problem is, this is when you introduce it.

Third Section (Act 2 or Act 3) *OPTIONAL*

The third section (either Act 2 or Act 3) is usually 3 scenes and lasts 5-7 minutes. This section is optional. Some pilots skip this section and instead make their first or second section (or both) on the longer side. You’d be especially likely to skip this section if your pilot requires more world-building due to a complicated setting or situation.

If you do include this section, it’s where you’ll do any combination of the following, depending on the needs of your story: introduce B-stories, explore the primary relationship, explain mythology, or complicate the protagonist’s problem.

If your show is about several characters with their own separate problems, you might choose to introduce B-stories in this section to tee up conflicts that will play out over the course of your season. These will not be lengthy, complicated scenes, because you don’t have time for that. You’ll need to introduce these stories very efficiently. For a good example of how to do this, watch the pilot of Search Party.

In some pilots, there’s a primary relationship that’s key to the show. In a show like Please Like Me that has a love interest at its core you might use this section to explore the primary relationship.

Please Like Me on Hulu / ABC (Australia)

If your show has a complicated mythology, like in the case of People of Earth, this section might be when you explain the mythology.

The last thing you might do in this section is complicate the protagonist’s problem if the main issue in your pilot is a problem the protagonist is individually facing.

Fourth Section (Act 2, Act 3 or Act 4)

The fourth section (either Act 2, Act 3 or Act 4) is usually 5-7 scenes and lasts 8-11 minutes. In this section, you’ll do some (but probably not all) of the following: resolve some problems, bring the protagonist’s main conflict to a climax, have a “moment of real” in which the protagonist reveals their vulnerability, complicate B-story situations previously introduced, culminate the main relationship, and escalate the protagonist’s problem in a way that’s caused by their own actions.

In some cases you’ll also have the protagonist choose to “step across the threshold of the series” and introduce a twist to launch us into the next episode, but sometimes those two things are done in the following section instead.

You’ll definitely want to resolve some problems in this section because there’s nothing more frustrating than a story that only asks questions and never gives answers. Leaving some of those mysteries unsolved and problems unfixed is necessary to bring people back next week, but to gain trust you need to show the audience that you are capable of resolving some problems and giving some answers.

For example, if it’s the kind of show that has a Problem of the Week along with a larger season- or series-long arc, this is where you’ll want to resolve this week’s problem.

This is the section where you bring the protagonist’s main conflict to a climax. Whether that’s an explosive fight with her daughter or a final showdown with the Monster of the Week (can’t it be both?), this is where things come to a head for this episode’s story (not the larger arc of the series).

In this fourth section, you’ll almost certainly have a “moment of real” in which the protagonist reveals their vulnerability. Depending on the tone of your show, this might be played half for laughs or it might be a truly dark moment. In this moment, the protagonist will often reveal a secret such as a fear, a weakness, or something in their past.

If you have B-stories in your pilot, this is the section where you might complicate B-story situations previously introduced.

If there’s a primary relationship in your pilot (not necessarily a romantic relationship), this is probably the time to culminate the main relationship by the characters either finally coming together or finally breaking apart.

This also might be the time to escalate the protagonist’s problem in a way that’s caused by their own actions. In other words, make them suffer, and make sure it’s their own fault.

Fifth Section (Act 3, Act 4 or Tag)

The fifth section (either Act 3, Act 4 or a tag) is usually 1 scene and lasts 30 seconds to 3 minutes. Usually this section is where the protagonist steps across the threshold of the series and a twist is introduced to launch us into the next episode, but sometimes this section is just a funny scene to end the episode if the threshold/twist happened in the previous section.

In very rare cases like Better Things, you might not have a threshold/twist at all because the show is “smaller” and lower concept, but keep in mind this is very rare and you will generally only see that in pilots created by showrunners with a proven track record. Your pilot should probably not be like that. But as always, listen to your own story.

If this is where your protagonist steps across the threshold of the series, what I mean is that they make an active choice to leave their ordinary world and step into the new world of the series. The audience should understand from this action what the show is going to be about (the second half of the logline) and that the protagonist is actively choosing it.

If you have a last minute plot twist that spins us into the next episode (and many pilots do, but not all), this is most likely when it will happen. This is usually a surprising piece of information revealed to the audience at the last minute that complicates what came before it and makes us anxious to see how it affects what happens next week.

***

You can now like this page on Facebook! Click the “Following” dropdown and select “See First” and “Notifications On” to get notified of new posts.