I’m interested lately in learning how to quickly establish distinct and intriguing or empathetic characters. I’ve been getting feedback that my screenplays dive into plot too quickly without giving the reader a chance to understand the world and care about the people in it. This is an unusual note since usually writers err on the side of taking too long to get to the plot!

My challenge now is to not overcorrect and create the more common problem: stories that are too chatty and lack forward motion (keeping in mind that “forward motion” doesn’t have to mean shootouts and car chases; it just means that something changes, however subtle).

The goal is to get into the plot quickly but to do so while setting up a rich world and introducing distinct, memorable characters. One way to do this is to show what the character is like through their actions that are part of the plot. As I’m watching movies and TV shows lately, I’m paying special attention to how the writers do this.

Heat (1995)

This week I watched Michael Mann’s Heat (1995), a movie that’s full of heists, bank robberies, and action-packed shootouts, but is also very long, very slow, very moody, and very character-driven. It’s also a movie that’s widely referenced by film buffs as one of the best crime movies of all time.

There’s a lot that can be said about this film, but what I want to write about today is how Mann introduces characters. Each character has a distinct personality that will bear relevance for the plot later, so it’s important that the audience gets the gist of them quickly. One tool Mann uses to accomplish this is what I’ve decided to refer to as the “three-point escalation.”

Each character has a moment pretty much immediately upon meeting them that gives a subtle indication of their personality. It’s enough to make us, as the audience, sit up and think, “This person seems like they might be <character trait>. I wonder if I’m right.”

Then, either later in the same scene or in that character’s next scene, they have a moment that’s a slightly bigger version of that. Now we’re putting the pieces together and we’re invested in solving the mystery of what this character is like. We now have a second clue that we’re on the right track. We’re paying attention.

Finally, either later in the same scene or in that character’s next scene, there’s a third moment that is much more dramatic and makes it unmistakably clear that we were right. We’re now fully invested in this character (even if we hate them) because we’ve solved the mystery of what makes them tick.

Mann does this to varying degrees with several characters, but I’m going to walk through the clearest example of this escalation with Waingro, the movie’s primary villain.

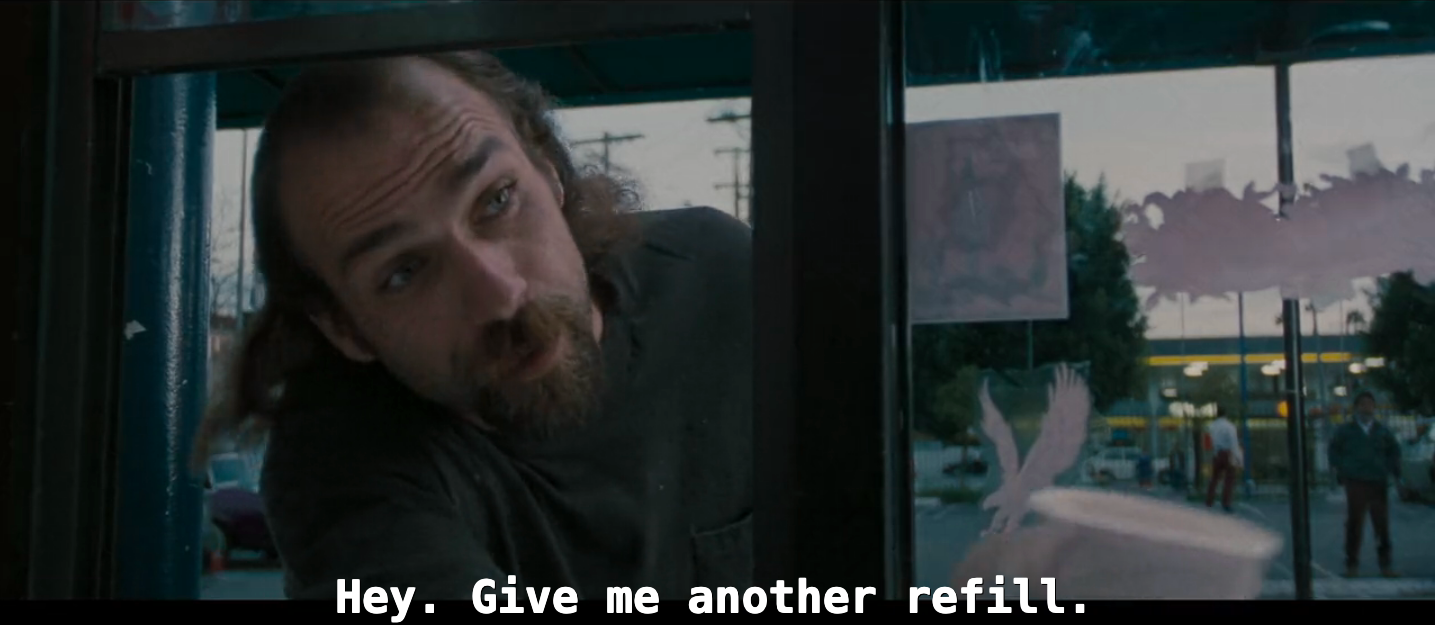

Step 1: When we first meet Waingro, he’s coming out of the outdoor bathroom of a cheap Mexican fast food place. He’s pulling on a shirt as though he’d changed clothes in the bathroom, or maybe bathed at the bathroom sink. He’s moving quickly, like a bull in a china shop. He shakes the liquid out of a to go cup he’s carrying and pokes his head and arm fully through the takeout window and demands “another” refill.

“Now he wants a refill,” one employee says to another, implying this guy was already a pain in the ass before we even got here. They take the cup. But instead of waiting for the refill, Waingro notices a semi-truck idling at the corner and he takes off without explanation.

This is a seemingly odd moment to include in the film but despite what a long movie this is, it doesn’t waste space on moments that don’t serve a purpose. Think about how differently this tiny interaction could have gone if Waingro was a different person. He could have come out of the bathroom fastidiously cleaning his hands, disgusted by the facilities. He could have asked for a refill apologetically and then told them to cancel it when he realized he needed to leave. He could spoken fluent Spanish to the cashier or flirted with him.

Instead, based on this very quick interaction, we already get the idea that Waingro is sloppy, impulsive, wired, and inconsiderate. But it’s not enough information for us to be sure we understand him.

Step 2: Waingro approaches the passenger window of the semi-truck and knocks. He tries to jump in, but the driver stops him and asks his name. The driver looks him up and down, clearly skeptical. Waingro introduces himself enthusiastically, but the driver is standoffish.

On the drive, Waingro chats loudly about the job they’re on their way to, constantly moving in his seat, asking too many questions. Finally the driver says, “Stop talking, ok, Slick?” After being so gregarious, Waingro now whips off his sunglasses and gives the driver a shockingly murderous glare.

This is an escalation of what we saw in the previous beat. It’s further confirmation that Waingro is sloppy, impulsive, wired, and inconsiderate. Now he also seems dangerous.

Step 3: During the heist, it’s clear to the audience which of the masked robbers is Waingro due to his signature long hair. It’s Waingro’s job to hold the three security guards at gun point while the robbery is completed, but he gets it in his head that one of the guards is looking at him funny, though the guard is clearly just in shock and has lost his hearing from the explosion. Waingro attacks the guard, and Cerrito (the driver from the truck) tells him to “cool it, Slick.”

Waingro begins breathing heavily, losing his cool, and finally kills the offending guard, turning this heist into a murder charge instead of just armed robbery. This forces the team to kill all three guards so as not to leave witnesses. Not part of the plan.

This third beat is a dramatic escalation that cements our understanding of Waingro: he’s a loose cannon who can’t tolerate any perceived slight and he doesn’t clear the bar of this highly disciplined and talented team.

If this third step (the killing of the guard) had been our first encounter with Waingro, we probably would have gotten the same general idea that he’s a loose cannon, but it would have felt out of nowhere and we might not have been sure how to interpret the scene. Maybe the guard was looking at him funny?

But by having those two previous beats first, we’re actively engaged in understanding his character, rather than passively observing him, and when this final escalation occurs, his character’s identity is now completely distinct to us from the others, which will be important for following the rest of the story.

I suspect that a lot of stories do a similar three-point escalation when introducing important characters. I’m going to be on the lookout for it.