I asked my friend Rick Stemm, a playwright and game designer who also happens to be a kickass fight choreographer, to write a guest post on how to construct awesome fight scenes on the page. Rick’s guest post below is full of concepts and tactics I’m excited to use in my next action sequence.

***

Crafting fight scenes, whether on the page or in the moment with actors, is one of my single favorite things to do. A well-crafted action scene can not only be that exciting setpiece that makes your show worth talking about, it can reveal truths about your characters and convey volumes of information in a satisfying way. Writing a good literal gut punch should cause a good figurative gut punch in your audience.

Like anything, this takes craft and practice. I am both a produced writer and certified Kungfu instructor and fight choreographer. That combo gives me some experience and perspective I hope you find helpful. The tips here are for writers, but I am also considering what I want to see as a choreographer to make my life fun and easy when I look at the script I need to bring to life.

Full disclosure – most of my writing of the last few years has been for theater and video games, so don’t worry too hard about this conflicting with any screenwriting rules. It’s not meant to be prescriptivist anyway, just some things to think about.

What Does Your Fight Need to Accomplish?

This is the first question you should ask of yourself when writing an action scene (I am going to say “fight” but it applies to chases and whatnot as well). And this question is really two questions:

- What does your fight need to accomplish for your plot?

- What does your fight need to accomplish for your characters?

The best fight scenes follow that old Kurt Vonnegut gem that every scene needs to move the plot along, reveal information about the characters, or both.

If you’ve outlined your story and are ready to write a fight, hopefully the plot needs should already be obvious. It can be active — Neo and Trinity fight their way through an army of security to rescue Morpheus. It can be reactive — just as the Terminator finds John Connor, the T-1000 shows up and they must escape. It can be purposeful — The Bride can’t get to Bill until she kills the other Deadly Vipers. It can be accidental — Simon Pegg & co. brawl with some teens in a pub bathroom and stumble into the terrible secret of the world’s end. Regardless, it moves the plot along.

But it can also reveal character. Likewise this can be done to more deliberately introduce a character — Sherlock Holmes (Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock (which hey I love the books but this movie is fun)) notices details and visualizes taking advantage of them before actually fighting. Or it can be a sudden reversal or growth at a key moment — Boromir fights off corruption and sacrifices himself to save the hobbits.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004)

Extra credit — there are questions I ask myself as a fight director that scripts don’t always answer, so I do in choreography. So bonus points if your script establishes the fighting style and skill of any characters involved in a fight. Are they badasses or pushovers? What weapons do they use — or does it matter? I don’t care what specific style of Kungfu a character knows (though I may borrow moves from a particular style when crafting that character’s moves), but it helps me to know how they mentally and physically approach a fight based on their background, as established in the story.

Here’s an example of a fight that pulls together all these things, from Pirates of the Caribbean:

Jack is in the blacksmith shop to break his manacles, Will is there to cover for his drunken boss. Plot established. We also see Jack’s resourcefulness and humor, and Will’s attention to detail and honor. All before the fight even properly begins. We also see their styles when the fight actually happens – Will’s intensely practiced swordsmanship, and Jack’s trickery.

Later:

What is the Tone?

Tone is a hard enough thing to master in your story, but it applies to fight scenes as well. It’s important to understand both the tone of the movie as a whole, and the tone of your fight scene. They don’t always match!

Kung Fu Hustle is a silly movie. A crazy good movie, but a very silly movie. All of its fight scenes are silly, even the ones invested with emotion. It’s consistent throughout. The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly is an epic adventure. Everything is on a grand scale and peppered with humor and twists. But its final showdown is anything but. Personal, patient, deadly serious, this contrast is deliberate and works to its advantage.

The tone applies to how you write a fight scene as well. Your descriptions and word choices are going to inform the action and choreography, even if they don’t describe the actual moves of the fight. Consider this example from possibly the greatest swordfight in all of cinema, in The Princess Bride:

The Princess Bride (1987)

Before it was released and became the greatest swordfight in modern movies, the script goes and calls it that in the description. Holy shit. And later:

It tells us nothing about the specific moves but everything about what is at stake, what we are supposed to see and feel. Sure, William Goldman might have a little more creative license, but even if you’re worried you don’t have that same kind of leeway, at least look to this for inspiration. (It is worth noting that it’s generally not recommended to have large blocks of text like this when describing stage directions, which includes fight scenes. Goldman has earned the right to get away with these things!)

Create an Arc

This should maybe have the sub-heading “Ok So How Much Detail Do I Actually Write In” because I’ll cover that too.

Movies have arcs. Scenes have arcs. Characters have arcs. Fights have arcs. There may be multiple beats to it, changes of dynamics of who is in control, attempting different tactics, learning, evolving. You don’t need to write down every move they use, but you need to make this flow clear.

Jackie Chan does this better than anyone. Hong Kong scripts are hard to come by, and even with an actual script it’d be hard to pull rules from it because Jackie often acts, directs, and choreographs, so who knows how much or little detail he wants. But even without the specific writing, I can tell you the arc of pretty much every Jackie Chan fight scene:

- Jackie is caught off guard, and not able to fight on ideal terms. He starts as the underdog and is just fighting to survive. We empathize with him.

- Jackie uses the environment in some creative way to get the upper hand. He begins to win and we’re rooting for him.

- Jackie gets beat on. It’s not enough, the enemies are too many or strong. He’s hurt, we see him bleed. We fear for him.

- Jackie remembers something he learned earlier in the movie and finds the strength or cleverness to eke out a victory. We feel he earns it.

I didn’t mention a single prop or Kungfu move here while breaking down a Jackie Chan fight. Even though those are used brilliantly, you don’t need to come up with them to have a brilliant fight. Humanize it. Give us the beats that make the fight a story itself.

Though if you have specific ideas for really great visual gags, or specific plot or character-critical moments that lead to these reversals, go ahead and write those in! A trick I use in a lot of my scripts is to put directions like “they fight until…” The ‘they fight’ is the job of the choreographer, with the ‘until’ followed by a great visual gag, a plot point that arrives to turn the tide of battle, a character defining moment that needs to happen — jobs for a writer.

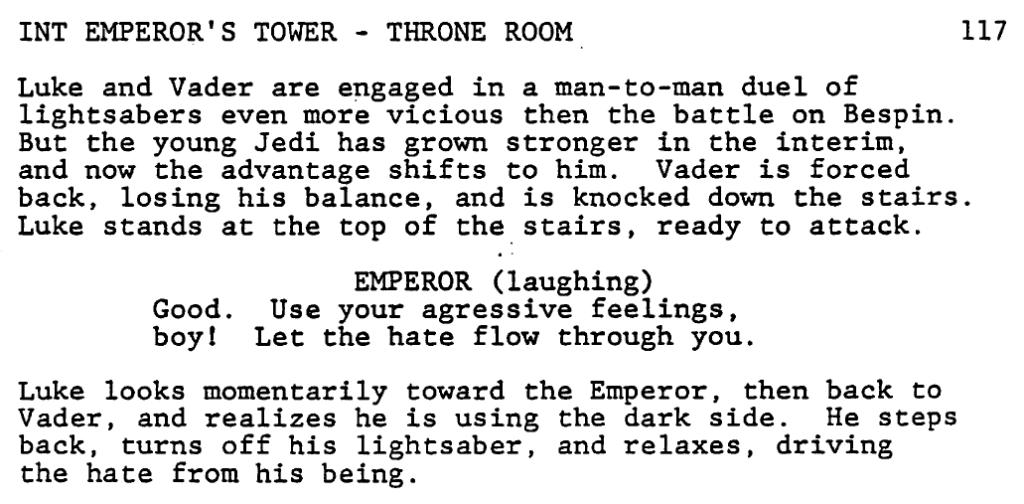

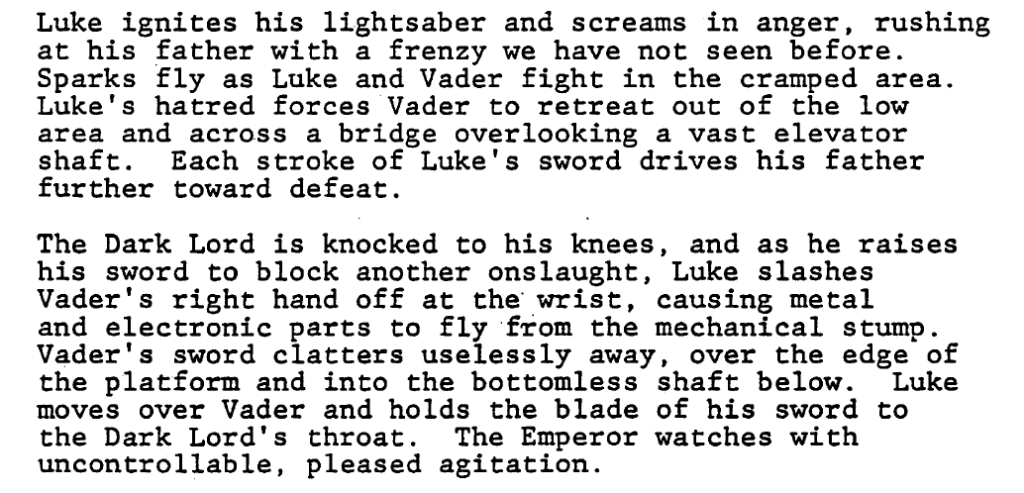

A great example of just enough direction, that also has excellent tone, and is highly plot-and-character motivated comes from arguably the single most important piece of pop culture in modern history — Star Wars. Here is the final fight between Luke and Vader in Return of the Jedi:

We understand the stakes – Luke and the Emperor battling over his very soul, light or dark, which we have come to believe is the key to the whole war between Rebellion and Empire. We are given the key moments of how the fight starts. But the fight itself doesn’t require a lot of detail:

The description is mostly Luke’s emotional state — starting from hatred, using it to win, realizing his hatred, pulling back.

Apart from the emotion, the detail focus on plot needs — Luke winning the fight, the fight moving toward the elevator shaft — which comes into play later — and the final, key moment. Why does it ignore all the sword-swinging and only specifically mention the cutting off the hand part?

Because that bit is the key to stopping the fight, connecting Luke and Vader, giving motivation to his final decision. That moment needs to be written because that moment drives the plot and character progression.

The cool part about all of this is you don’t need to be a martial artist to write great fight scenes — you just need to take your non-martial art skills of plot and character, tone and progression, and apply them to fight scenes as well. Us Kungfu guys will do the rest.

***

Rick Stemm is a playwright and game designer based in San Antonio, TX. Check out his project Heroes Must Die which combines video games and live theater.

***

You can now like this page on Facebook! On the Facebook page, click the “Following” dropdown and select “See First” and “Notifications On” to get notified of new posts.