The opening scene of a screenplay is a sales pitch to convince the reader to stick around for the rest of the script. Is there a formula to writing a great one? Are there common elements they all share? Are they usually a particular length?

To answer these questions, I watched the opening scenes of 80 movies from a wide variety of genres. Most of these films are critically-acclaimed. Some were recommended by friends because their first scene was especially memorable.

What I learned was interesting. Of course there isn’t a single unifying formula for a great opening scene, and length varied a lot more than I expected, but almost every opening scene I watched did fall into one of five categories and almost all opening scenes shared several common elements.

What is a Scene?

Before we can talk about great opening scenes, let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what a scene is.

A scene is the smallest unit of story in a script. Here are some common elements often used to define a scene:

- It takes place in a single location

- It takes place in a single block of time

- It represents a single problem with a beginning, middle, and end that can stand alone as its own understandable mini-story

But there are many counterexamples to these definitions.

For example, you could have a single conversation start in a parking lot, continue in the car on a drive, and resolve when the characters arrive at their destination. It’s a single block of time and a single problem with a beginning, middle, and end, but it takes place across multiple locations.

Similarly, you could have two unrelated conversations taking place in a single room at a party. It’s a single location and a single block of time, but it’s two unrelated problems with their own beginnings, middles, and ends.

Last, you could have a conversation that starts in bed, then the characters fall asleep, eight hours pass, and we come back to them in the morning as they wake and finish their conversation. It’s a single location and a single problem with a beginning, middle, and end, but it takes place over two blocks of time.

In each of these examples you’d need to call these separate scenes in a script for production purposes, but for storytelling purposes, you might think of them as a single scene. This gets even more complicated with montages, which we’ll see below are a surprisingly common form of opening scene in movies.

Scene vs. Sequence: What’s the Difference?

Beyond a scene, we also have something called a sequence. Again, this gets muddy, but a sequence is a slightly larger unit of story, composed of multiple scenes that link together continuously to show the introduction and resolution of a problem before the story cuts away to a new problem. (Note that when I say “resolution,” I don’t mean that the problem is solved, just that the question the problem raised now has at least a tentative answer.)

You could argue that a montage is really a sequence not a scene, or that some of my examples above of rule-breaking scenes are actually sequences. It’s all semantics, so define these terms in the way that’s most useful for you. At the end of the day, we’re trying to tell a good story, not pass a pop quiz.

The Godfather Part II (1974)

For an example of what I would call a sequence, look at the beginning of The Godfather Part II (1974). The first scene of the movie is a very short, almost wordless scene in which young Vito’s brother is killed by a local mafia lord during his father’s funeral in Sicily. In the next scene, Vito’s mother brings him to Don Ciccio, the mafia lord who killed Vito’s father and brother, to beg for mercy. Don Ciccio refuses, Vito’s mother attempts to take him hostage, she is killed, and Vito escapes.

This entire sequence is only about four minutes long. It’s two separate scenes because the events take place in two separate locations and some time has passed offscreen between them (though maybe only an hour or so). But most importantly, it’s two separate scenes because each scene has its own beginning, middle, and end. The first scene starts with a funeral procession and ends with Vito’s brother being killed by Don Ciccio. The second scene begins with Vito’s mother begging Don Ciccio for mercy and ends with her being killed as Vito escapes.

But together these two scenes make up a larger sequence that involves the introduction and resolution of a single question. The question is: “Will Don Ciccio spare Vito’s life?” The first scene introduces the question when Vito’s brother is killed by Don Ciccio at his father’s funeral; the sequel answers the question when Vito’s mother begs Don Ciccio for mercy and he refuses. The problem isn’t solved, but it’s resolved — we now have an answer to the question. The answer is no.

You could argue that the section after these two scenes (Vito escaping Corleone with the help of townspeople) is part of the same sequence, but to me that’s a new sequence with a new question that was not introduced in the previous sequence. The question the second sequence asks is: “Will Vito successfully escape Corleone?”

Who Cares?

Does it matter how we define a scene or a sequence? In a way, no, it doesn’t matter at all. If you’re telling a great story, it doesn’t matter if the whole movie is a single scene or five acts or a hundred sequences or however you want to think of it.

But it can be helpful to think about these things if part of your story feels unsatisfying and you can’t figure out why. You can ask yourself: does this scene have a beginning, middle, and end? Is it part of a larger sequence that asks and answers a question? Does the end of my scene or sequence pose a new question to pull us into the next scene or sequence? If the answer to any of these questions is no, that might be the problem.

It’s particularly important if the scene or sequence that feels unsatisfying is the very first one of your script.

Types of Opening Scenes

After analyzing the opening scenes of 80 movies, I found they all (with just five exceptions) fit into one of the following categories:

- Prologue (32%)

- Prologue montage with voiceover (16%)

- Prologue scene without voiceover (16%)

- Inciting incident (25%)

- Day in the life (24%)

- Exciting day in the life (13%)

- Uneventful day in the life (11%)

- Cold open (11%)

- Flash forward (8%)

Note: almost every movie I watched had a long string of wordless shots that ran under the opening credits. I did not count this section of the film as part of the opening scene.

Prologues

For this purpose, I define a prologue as a montage or scene that’s meant to succinctly communicate important backstory that occurred before the events of the film.

Prologue Montage with Voiceover

Sometimes this prologue is a montage with voiceover narration that dumps a ton of exposition on the audience at once. Just about every screenwriting guru on Earth will tell you to avoid voiceover like the plague, but it’s surprisingly common even in critically-acclaimed films and can be effective when used thoughtfully.

Prologue montages with voiceover are especially common in fantasy movies and epics because there’s so much complicated history and world-building that the audience needs to understand, but they’re also common in films that hinge on the unique voice and point of view of the main character, especially if the main character will turn out to be a somewhat unreliable narrator.

Raising Arizona (1987)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of Raising Arizona (1987). This montage is entertaining due to the unique style and character voice. This opening makes it very clear what kind of movie you’re about to watch and it really adds something to the film instead of just feeling like a lazy way to dump a bunch of info on the audience.

Interesting side note: Ready Player One (2018) begins with a 10-minute prologue montage with voiceover, but I read an earlier draft of the screenplay a few years ago that opened with an inciting incident scene instead, which I liked so much better.

Examples: Raising Arizona (1987), Legends of the Fall (1994), Clueless (1995), A Simple Plan (1998), American Beauty (1999), The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), Amélie (2001), Love Actually (2003), The World’s End (2013), Arrival (2016), Love, Simon (2018), Ready Player One (2018)

Prologue Scene without Voiceover

Prologues don’t always have voiceover. Sometimes instead it’s a flashback scene that reveals a pivotal moment in the past (usually childhood) of an important character.

Flashbacks, like voiceover, are dangerous territory — they almost always lack tension because the events of the scene have already transpired so the outcome has no sense of immediacy. They also often involve characters that won’t be present in the rest of the story (or are played by different, younger actors), which can be confusing to the audience.

But when done well, these types of prologues can be very effective at catching us up on important backstory and building sympathy (or lack thereof) for a character.

Inglourious Basterds (2009)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of Inglourious Basterds (2009). It’s an incredibly long scene, but it’s extremely tense from start to finish. This scene introduces the antagonist, sets up the motivation of a main character, situates you in the world and tone of the movie, and expertly wields subtext to create suspense and interest.

Examples: The Godfather Part II (1974), The Sixth Sense (1999), Capote (2005), Zodiac (2007), Inglourious Basterds (2009), Star Trek (2009), Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), Lion (2016), Manchester By The Sea (2016), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017), and Black Panther (2018)

Inciting Incident

In many movies, there are about ten minutes or so of setup before the movie’s inciting incident (the first event that kicks off a profound change in the protagonist’s life), but in some movies (more than a quarter of the ones I watched), the inciting incident happens on practically the first page.

This type of opening scene introduces the inciting incident that sets the story into motion. It could be a wedding, a funeral, or an apocalypse. Maybe the main character is released from prison, they start a new job, they move to a new house, or they learn about an opportunity. Maybe they win the lottery or meet the love of their life. I was actually surprised how often this inciting incident happened in the very first scene of a movie without any setup before it.

There Will Be Blood (2007)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of There Will Be Blood (2007). In the first minute of the film, the main character discovers silver in his mine, which leads to everything else that happens in the film, but there are a few special things about this scene:

- It sets up the plot of the movie very efficiently and everything is communicated visually, not through dialogue.

- It’s incredibly tense. There’s a part in the scene in which a literal stick of dynamite is counting down to an explosion. There are also elements of mystery and surprise.

- Though there is almost no dialogue (he says a few words out loud to himself at one point), by the end of this scene you understand exactly who this character is, including his strengths and weaknesses that will drive the rest of the story.

Examples: Back to the Future (1985), Aliens (1986), Die Hard (1988), Dead Poets Society (1989), The Silence of the Lambs (1991), Se7en (1995), Ocean’s Eleven (2001), Training Day (2001), There Will Be Blood (2007), The Gift (2015), Moonlight (2016), The Witch (2016), Nerve (2016), Hello, My Name is Doris (2016), The Big Sick (2017), The Florida Project (2017), Call Me By Your Name (2017)

A Day in the Life

A “Day in the Life” opening scene is a scene that introduces the main character — usually revealing a key strength and key liability — and shows what their life is like before it’s changed by the events of the film.

Like prologues, there are two subtypes within this category.

Exciting Day in the Life

Some movies open with our main character or characters in media res in an exciting situation that is typical for them before the events of the film change their life forever. But when I say it’s a “typical day,” I don’t mean a scene of them eating cereal in front of the TV. It’s an especially exciting or dramatic moment in their everyday life. Sometimes this scene will turn out to tie in with the larger plot of the movie but often it has no relation to the main plot, or has only a tangential connection.

You most often see these types of scenes when the main character has an exciting job: a spy, a cop, an assassin, a bank robber, etc., but not always.

Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Offensive stereotypes of indigenous people notwithstanding (yikes), this is one of the greatest opening scenes in the history of cinema. It sets up the tone and genre of the movie beautifully, tells you just about everything you need to know about the main character, and is very exciting and well paced. You know Indy survives the ordeal because there’s an entire film franchise about him but even still you’re on the edge of your seat worrying whether he’ll make it out alive.

Examples: The Wizard of Oz (1939), Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Men in Black (1997), Out of Sight (1998), Bad Boys II (2003), Spectre (2015) (in fact, pretty much any Bond movie), Green Room (2016), Baby Driver (2017), Lady Bird (2017), Logan (2017)

Uneventful Day in the Life

Other times, a movie opens with a “day in the life” scene that’s not that dramatic or exciting at all. It’s difficult to pull off an uneventful scene like this in a way that’s interesting and suitable for the movie. Many writers open their stories this way by default (a screenplay starting with a character waking up in bed is overdone to the point of cliché) but it’s better when chosen with intention.

The key to making these scenes work is to have something fresh and unusual about the setting, situation, dialogue, or characters. The scene usually introduces one or more main characters in a way that makes them sympathetic or at least intriguing. Scenes like this usually (but not always) establish the tone and genre of the movie and illustrate the overall theme of the film.

The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017)

I didn’t especially love any of the opening scenes I screened in this category, but if I had to choose one it would be The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). This is almost a cheat because this scene proves the distinction between “exciting slice of life” and “uneventful slice of life” can be blurry. The movie begins with a closeup of a real open heart surgery, which is shocking to the audience and has life or death stakes for the patient, but it’s not presented as suspenseful in the movie. In the context of this story, it’s just a day at the office for the main character. We don’t even find out if the surgery was successful, and the scene ends with the surgeon having an intentionally mundane conversation with the anesthesiologist about watchbands. The scene isn’t about stakes; it’s about theme and character and setting an expectation of tone for the movie.

Examples: Gone with the Wind (1939), Carrie (1976), Blue is the Warmest Color (2013), Fences (2016), Logan Lucky (2017), Landline (2017), A Ghost Story (2017), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017)

Cold Opens

When we think of cold opens, we usually think of television. A cold open in television, sometimes called a teaser, is the section of an episode that’s shown before the opening credits. (Not all episodes have a cold open; some start with Act 1.)

Most common in horror movies, crime thrillers, and action flicks, the main purpose of a cold open is to grab the audience’s attention and establish genre elements before beginning Act 1, which will be a “before picture” of the characters’ lives and therefore the least exciting part of the film. But even outside of these genres, a cold open can demonstrate the strength of a powerful antagonistic force, as it does in Spotlight (2015).

A cold open in film almost never involves the movie’s main characters; this scene is narratively separate from the events of the story, though it provides important context.

The Lobster (2016)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of The Lobster (2016). It’s unique, it’s surprising, it sets the tone of the movie, and it creates a question in the audience’s mind that will be answered later.

Examples: Jaws (1975), The Last Boy Scout (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), Scream (1996), The Fast and the Furious (2001), Spotlight (2015), The Lobster (2016), Get Out (2016)

Flash Forward

A “flash forward” opening is when a movie starts with a scene in the present (or at least the “present” in the timeline of the film) and then the rest of the movie (or most of it) takes place in the past leading up to that opening moment.

This has become common to the point of cliché in television pilots, though it’s a gimmick I personally enjoy. It was probably made most famous on television by the pilot of Breaking Bad (2008). These flash forward openings often have voiceover narration, but not always.

The Prestige (2006)

My favorite example of this type is the opening scene of The Prestige (2006). That scene makes great use of voiceover narration to establish a theme of the film, while also teasing the audience for an exciting climax and presenting some mysteries to be solved later (like what’s the deal with all the hats).

Examples: Titanic (1997), Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003), The Prestige (2006), The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), Carol (2015), Wonder Woman (2017)

Elements of an Opening Scene

There is no set length for an opening scene. Of the scenes I watched for this analysis, the shortest was about 30 seconds and the longest was 19 minutes. The median length was three minutes and 70% of them were five minutes or shorter.

Almost half of the scenes I watched were structured like a short film, by which I mean they had a setup in the beginning, a middle with rising tension or complications, and at the end usually some sort of twist, surprise, or reversal.

The first scene usually introduces at least one main character, but sometimes the characters in the first scene aren’t in the rest of the movie at all.

Common elements in most opening scenes (this isn’t a checklist — every opening scene doesn’t have to have all of them):

- Introduces the protagonist in a way that communicates their main skills, qualities, quirks, and weaknesses efficiently and visually.

This one is very common for scenes that feature the protagonist. By the end of the first scene, the audience can often see the good and bad of this character and is already getting an inkling for how they are going to screw things up and why they need so badly to change (which they may or may not ever successfully do, depending on what kind of story you’re telling).

- Introduces the world.

Where are we? When are we? If it’s a period piece, indications of the time period are introduced in the first scene. If the world has a geography that the viewer needs to understand (even if it’s just the hallways of a high school), the first scene will sometimes intentionally orient the audience to this map. If there’s magic in the world or strange rules or customs, we’ll likely see those right away too.

- Offers audiences a “before” picture to later compare with the “after.”

Some screenwriting gurus will tell you this is required, but it’s not. It is common though. Very often the first and last scene of a movie will mirror each other in some way to illustrate how the protagonist has changed. So if you know how your movie is going to end, that might give you an idea for how it should start.

- Presents a “save the cat” moment for the protagonist, even if it’s very subtle.

You’re probably familiar with the concept of “saving the cat,” which comes from the late Blake Snyder. It refers to a moment in many movies in which the protagonist does something kind or selfless (like saving a cat) to show the audience that they are a good person, even if they otherwise act like an entitled jerk. About 27% of the opening scenes I watched had a moment like this, even if it was very subtle.

For example, in the opening scene of Baby Driver, Baby is literally a getaway driver for a bank heist — not a noble occupation — but there’s a brief moment when he lowers his sunglasses to get a better look through the window at the heist because Griff is waving his gun around and you get the sense from Baby’s expression that he might be concerned about the hostages. It’s quick and subtle but it’s enough.

- Tense and suspenseful.

Over half of the opening scenes I watched (even some quiet indie dramas) were tense, suspenseful, or dramatic, but what’s really surprising is that almost half of the scenes were not tense and suspenseful! Opening with a scene of conflict or danger can suck people into your story quickly, but it’s not the right start to every movie.

- A surprise or big reversal.

It’s common for opening scenes to contain at least one surprising revelation or an unexpected reversal of fortunes — a character isn’t what she seems, a character seems like he’s going to get what he wants but then he doesn’t, etc.

- Sets the tone and genre of the film.

Almost all opening scenes I watched established the tone and genre of their film but occasionally you’ll see one that doesn’t. Two examples I can think of off the top of my head are Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Logan Lucky (2017), both of which have opening scenes that don’t really reflect the genre and tone of the rest of the film.

Cliché Ways to Begin a Screenplay

- Main character waking up in bed

- Main character having breakfast with their family and/or getting the kids off to school

- Main character jogging

- A fake-out (we think something serious is happening but it turns out to be a dream or a drill or a scene from a movie-within-the-movie)

- A therapy appointment, a job interview, a parole hearing or some other similar way of getting across a bunch of exposition through dialogue

- A newscast, an office PowerPoint, a debriefing, or some other similar way of getting across a bunch of exposition through a presentation

- Childhood flashback

- Voiceover narration

It’s not that any of these are inherently bad and should never be done. There are great movies that use each of them. Just make sure it’s really serving your story and isn’t just the first cliché idea that popped into your mind.

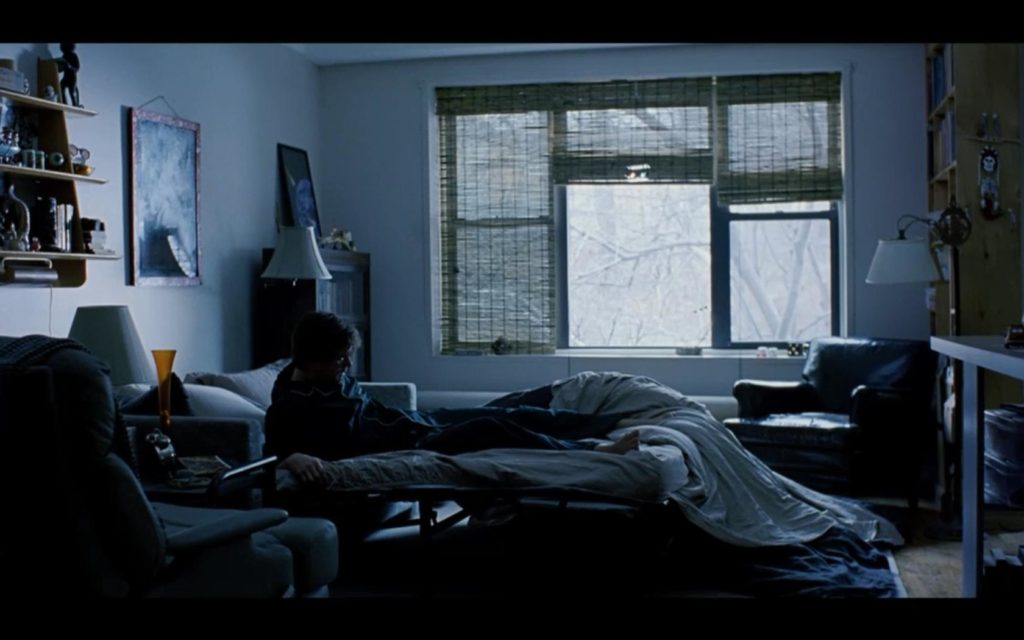

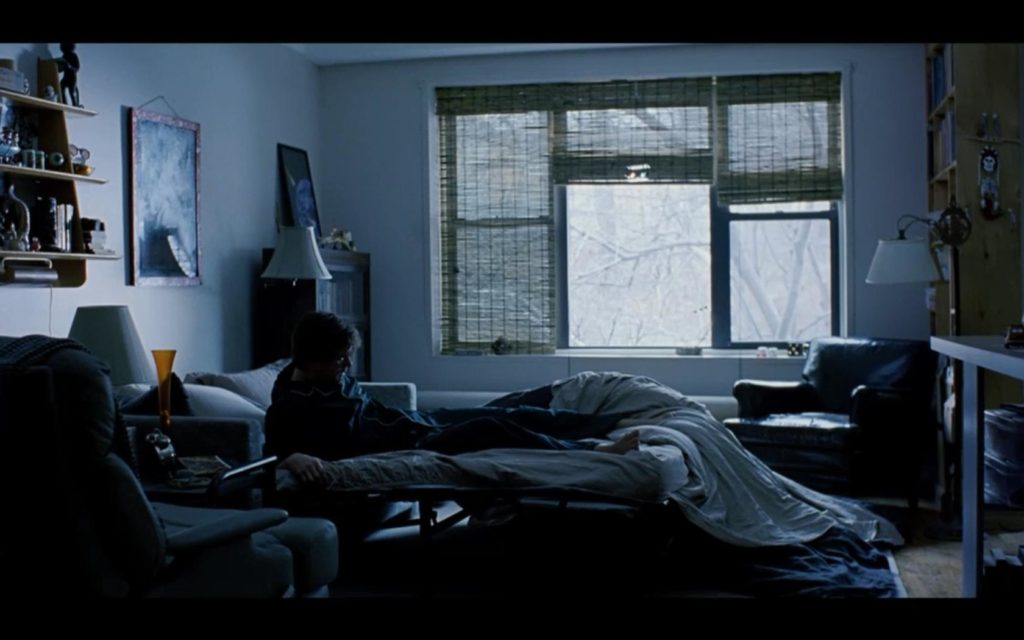

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

For example, a “main character waking up in bed” opening can be a good choice for a movie that’s about sleep or waking up or monotonous routines. The key is to choose it thoughtfully.

As another example, nine out of ten screenwriting gurus will tell you to never open a script with voiceover narration because it’s lazy, but it’s surprisingly common in commercially-successful and critically-acclaimed movies. There was voiceover narration in the first scene of more than 20% of the movies I watched. That’s more than 1 out of every 5 movies!

I still don’t recommend it because so many readers have a knee-jerk negative reaction to it and most of the time it really is being used out of laziness. Find a more creative way to communicate your exposition (or question if it really needs to be communicated at all), and let the studio convince you to add in voiceover later, after they’ve given you lots of money.

What to Do With This Information

If you’re struggling with the first scene of a script you’re writing, go through each of the types of opening scenes above and brainstorm one for your script that would fit in that category. Go ahead and list the most cliché ideas first, but then try to push yourself to think of a few more that are more surprising. You might come up with something interesting that you wouldn’t have otherwise thought to do.

Also, remember that you can always go back and write a new opening scene later. It might be easier to see what that opening scene needs to be after you’ve finished a first draft of the entire screenplay.

Finally, if your first scene doesn’t fit any of the categories above but it’s working for you and your readers, that’s great. Out of the 80 films I watched for this analysis, I came across five opening scenes that didn’t neatly fit any of the above categories. Those movies were The Karate Kid (1984), Steel Magnolias (1989), Schindler’s List (1993), Election (1999), and The Truman Show (1998), and three of those movies had an over 90% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, so though it may be rare, it’s definitely possible to write an opening scene that doesn’t fit in any of the above categories and still have a great script.