Story Structure Breakdown Series

In this series, I’ll breakdown the timestamped story beats of several critically acclaimed, commercially successful films and TV episodes and see how they stack up against four popular narrative formulas:

- Syd Field’s version of the three-act structure

- Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat

- Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey

- Dan Harmon’s Story Structure 101

(The last two are both based on Joseph Campbell’s concept of the Hero’s Journey.)

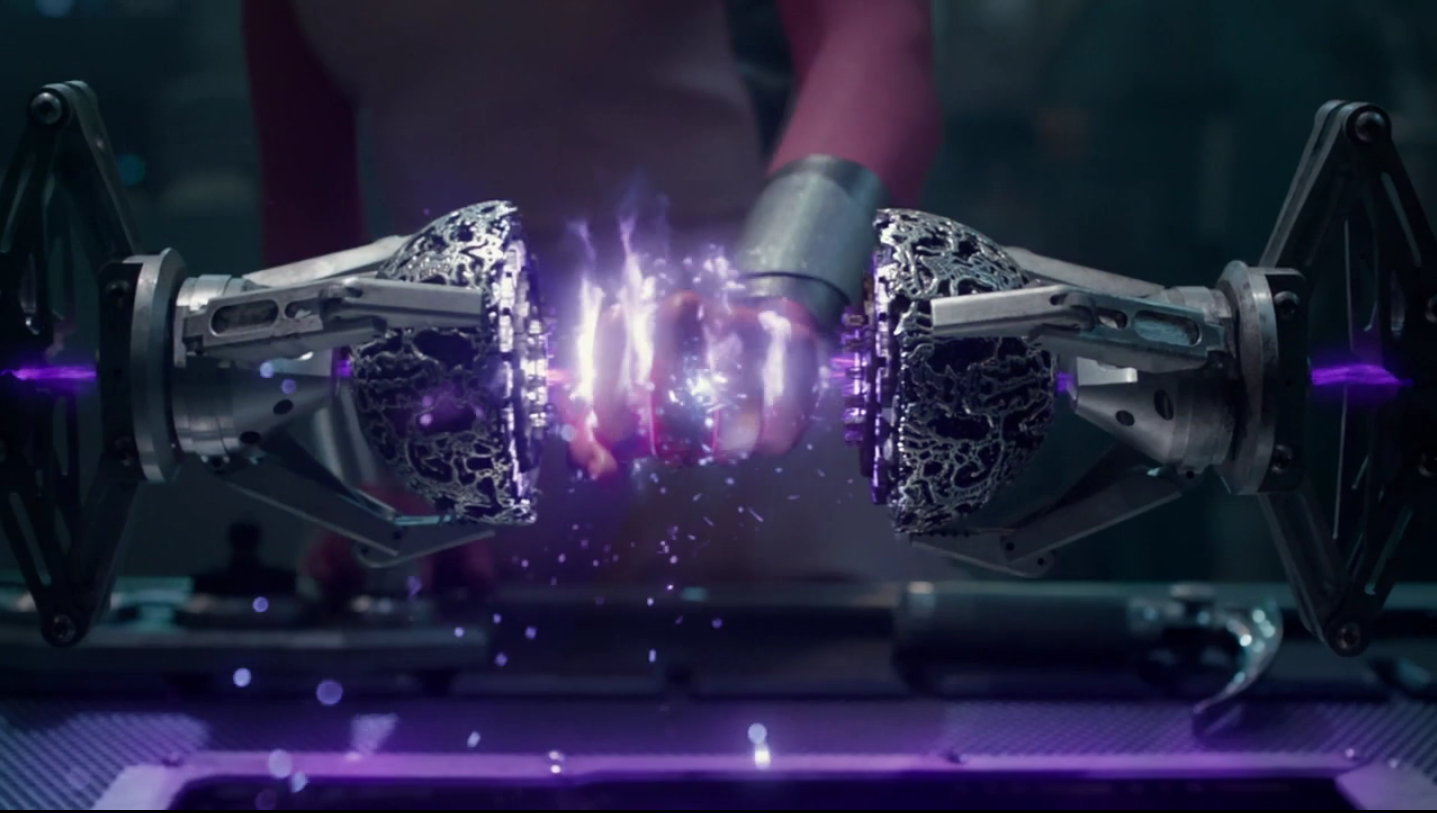

Guardians of the Galaxy

The first film I’ll cover is the 2014 Marvel hit Guardians of the Galaxy. I chose this movie because it was commercially successful (it earned $94,320,883 its opening weekend) while also being critically acclaimed with a 91% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a score of 8.1 out of 10 on IMDB.

When I saw this movie in the theater, I was struck by how well plotted it was – it’s funny, exciting and emotionally moving with no boring parts, and it has a satisfying resolution. So I was curious to see how the story beats would line up with popular story structure timelines.

For timestamp and story percentage purposes, I excluded the opening and closing credits, including the bonus scenes that play during the closing credits, and also the short prologue that plays before the opening credits. While important for the viewer to see, I felt that the prologue existed outside the main narrative arc. I started the film when adult Peter Quill (Chris Pratt) lands on the planet Morag to search for the orb. Based on this cut, the movie “starts” at timestamp 04:24 and runs for 110 minutes. My timestamps came from the version streaming on Amazon Video.

Syd Field’s Three-Act Structure

I’ll start with the basic three-act structure as interpreted by Syd Field. In this structure, Act I should fill the first 25% of the story, which means it should end at minute 32, and the Inciting Incident should occur halfway through Act I (at the 12.5% mark).

Syd Field defines the Inciting Incident as the event that sets the main story in motion. I felt this moment was when Gamora, Rocket and Groot all simultaneously jump Peter on Xandar (Gamora to steal the orb, Rocket and Groot for the bounty on Peter’s head). This is when the four of them meet and it’s what leads to them being arrested and taken to the Kyln space prison together.

Based on Syd Field’s formula, this moment should take place around minute 18, which turns out to be exactly when it happens.

Syd Field says that Act I ends when the protagonist makes the decisive choice to pursue the first major goal of the story. At this point, the story twists in a new direction that the hero can no longer turn back from.

I felt this moment was when Peter chooses to save Gamora from Drax and suggests that she, Rocket, Groot and he should join forces to break out of the prison and sell the orb to the highest bidder. This is an important moment for the characters’ inner journeys because it’s when all four go from going it alone to trying to work with a team. It’s also a moment when the protagonist makes a definitive choice that sets a story in motion that he cannot turn back from.

Syd Field thinks this moment should happen at minute 32, which is exactly when it happens.

According to this formula, Act II should run from minute 32 until minute 87, with the Midpoint occurring at minute 59 and what Field calls First Culmination happening just before it.

The first part of Act II is when the protagonist pursues his goal, encountering obstacles but not yet aware of how truly difficult the journey will be. The First Culmination is the moment when it seems like the hero has achieved his goal, then everything falls apart leading to the Midpoint.

The First Culmination is when the teammates finally arrive at The Collector’s lab and are about to sell him the orb. He’s explained the significance of the item and is about to pay them for it and it seems like the story could be about to end. This scene happens between minutes 56-59, which is exactly when Syd Field says it should.

The Midpoint is when it all goes south – something unexpected happens that twists the story in a new direction, proving just how difficult this journey will really be. In the first half of Act II, the protagonist tries to solve the problem in a way that’s similar to how he normally would, but after the Midpoint it begins to become clear how much the hero will need to learn and grow to achieve his goal.

I felt the Midpoint was the moment when The Collector’s attendant grabs the infinity stone, blowing up the lab and killing herself and The Collector and nearly killing everyone else. This is the moment when the heroes learn how powerful and terrifying this orb they’re carrying really is. It’s also the moment that ruins their chances of selling the orb as planned. The story has twisted in a new direction and they will need to take a different approach. Stakes are raised and the story’s direction changes. This moment happens at exactly minute 59, just as Syd Field said it would.

The rest of Act II is predicted to last from minutes 59 to 87. Screenwriter Doug Eboch says that this half of Act II often contains what he calls fireside scenes, chalkboard scenes and emotional revelations. All three of those appear between minutes 59 and 82 in this movie.

Syd Field says that Act II ends with another reversal that spins the plot in yet another new direction. Typically, this is the moment when the hero finally realizes the true solution to his problem and it’s a solution that involves the synthesis of everything he’s learned. It’s also a solution that seems nearly impossible, but is unfortunately his only hope. This moment occurs when the team sets their plan in motion to warn Nova HQ of Ronan’s attack and then kill Ronan themselves. This happens at minute 82, which is a few minutes earlier than when Syd Field thinks it should happen (minute 87).

The rest of the film is Act III, which Syd Field says includes the Climax (Second Culmination), which is the point at which the story reaches its maximum tension (the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist) as well as the Denouement, which is the brief period of calm at the end of the film. He thinks this act should last between minutes 87 and 114 in this film, but it actually begins at minute 82. This act includes the Climax (the moment when the team joins forces to defeat Ronan once and for all) as well as the Denouement (the calm period at the end when the team reflects and looks forward to their next adventure).

In a future update of this post, I’ll analyze the structure of this film based on Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat formula, Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey, and Dan Harmon’s Story Structure 101.

***

You can now like this page on Facebook! Click the “Following” dropdown and select “See First” and “Notifications On” to get notified of new posts.